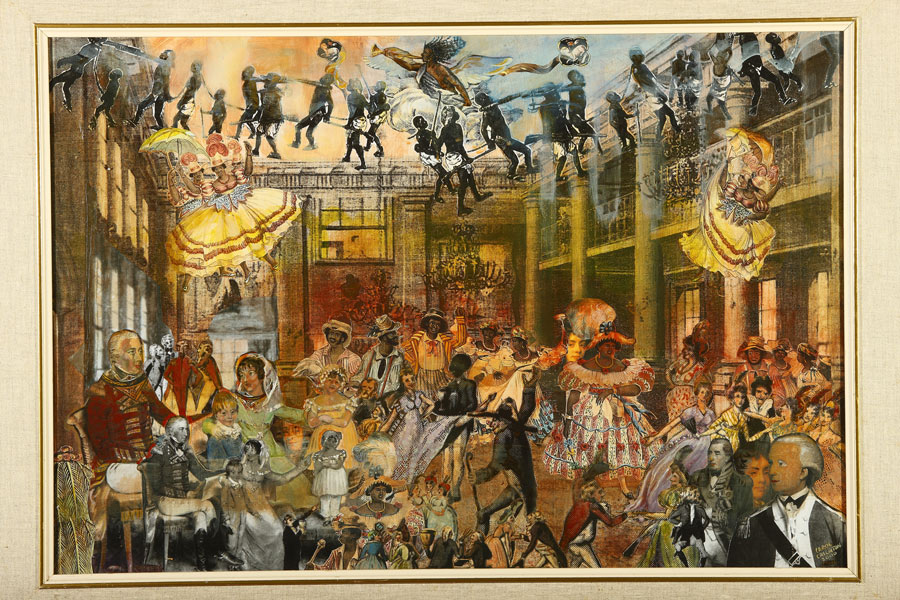

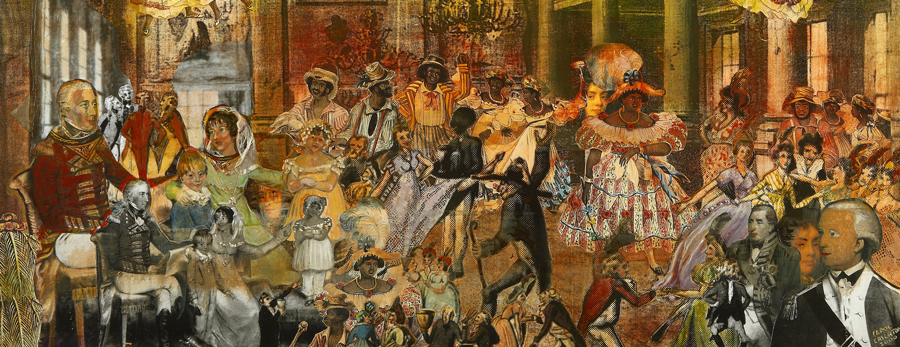

I did a double take when I saw this work hanging in a Montego Bay exhibit last year. Admittedly, my interest was more than casual. I was writing Voices Echo at the time and visiting Jamaica to flesh out my research. Many of the images in the collage echoed familiar themes and historical details in my novel.

The Nugents Entertain at King’s House © Carol Crichton

Still, it’s striking, isn’t it? The work was on display at Montego Bay’s Sangster International Airport and curated by Gilou Bauer. The artist, Carol Crichton, managed to capture the essence of Jamaica’s complex, tapestried past in this one collage, and she has graciously allowed me to post it.

As her website explains, Ms. Crichton’s work “considers issues of identity and history as found in the nexus of bloodlines and cultures that is the West Indies.” Her depiction, blending realism and caricature, offers a glimpse of the people as well as a social critique of the period.

It’s worth noting that such a diverse gathering would not have occurred in the King’s House during the Nugents’ time in residence. Ms. Nugent wrote of receiving “black, brown and yellow ladies” only in her private rooms,1 and missionary historian W.G. Gardner wrote that it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that “colored guests” were invited to social functions at the King’s House.2

The Nugents Entertain at King’s House

The King’s House referenced in the image was in Spanish Town. It served as the Governor’s residence from about 1762 until 1872 when the seat of government transferred to Kingston. Only the façade of the original King’s House remains; fire destroyed the building in 1925.

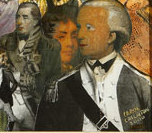

Governor George Nugent, who was governor from 1801 through 1805, and his wife Maria are pictured twice in the bottom left corner—once in color and once in black and white (parceled out and shown at left).

Crichton explains that their family portrait appears twice, small and large, to emphasize that though they were mere mortals, “in the context of the Colony” they were “larger than God, embodying the Crown.”

The room pictured is the great saloon, and it occasionally doubled as a ballroom when not being used for official business. Mrs. Nugent referred to it as the ‘Egyptian Hall’ in her diary, a generic 18th-century term for large rooms characterized by columns on one side with a gallery above. Both the gallery and the columns are on the right side of the image.

The chandelier still exists and is now hanging in the National Library in Kingston.

The chandelier still exists and is now hanging in the National Library in Kingston.

Admiral Duckworth and the Earl of Balcarres, both serving in Jamaica in the King’s House heyday, are pictured in black and white in the lower right corner. There’s even an image of pirate-turned-governor Henry Morgan tucked in.

Admiral Duckworth and the Earl of Balcarres, both serving in Jamaica in the King’s House heyday, are pictured in black and white in the lower right corner. There’s even an image of pirate-turned-governor Henry Morgan tucked in.

The Revelers

Ms. Crichton explained the women positioned above Duckworth and Balcarres are part of a

derisive cartoon mocking the white creoles and their “balls and ostentatious excess.” There’s no shortage of 18th-century caricatures mocking the white West Indies creoles’ ostentatiousness; the caricature she referenced is entitled A Grand Jamaica Ball! and likely dates from Balcarres’ term as governor.

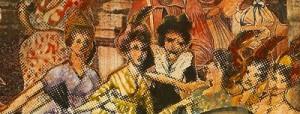

This woman features prominently in the collage. She’s the “Queen” of the “Set Girls,” and is from one of Jamaican artist Isaac Belisario’s 1837 lithographs.

This woman features prominently in the collage. She’s the “Queen” of the “Set Girls,” and is from one of Jamaican artist Isaac Belisario’s 1837 lithographs.

Note the smiling Queen carries a cow-hide whip in her right hand. Unlike an overseer’s whip, it’s festooned with three bows. Belisario wrote that she exercised the whip “with unsparing severity,” the ribbons being a mockery of “the purpose to which it [the whip] is not unfrequently applied—the appendage is highly necessary for the preservation of order in her corps de ballet.” 3

Crichton also placed Belisario’s Red Set Girls in the “sky”, as “whimsical anachronistic shades of Mary Poppins.”

The French Set Girls with the Jaw Bone Musicians (Belisario)

In actuality, the Sets danced and paraded through Kingston’s streets at New Year, decked out in all their finery—most of which was supplied by their masters, mistresses or patrons. In his 1818 Journal of a West Indies Proprietor, Matthew Lewis recorded the Sets were first sponsored by rival military units stationed in Jamaica.4 Ms. Crichton noted that some parade characters mocked their oppressors; others retained African ritual symbolism in their dance.

The “John Canoe” festivals, as the elaborate holiday processions were known, were created by the enslaved Africans. The white colonists viewed the secular5 celebrations as a harmless, if somewhat intimidating, release of simmering hostilities. The celebrations, often called Jonkonnu, occur to this day.

The Enslaved

And finally, the enslaved, whose labors were chiefly responsible for the colony’s vast wealth. Crichton’s placed them up near heaven, dispiritedly trudging the ceiling’s perimeter, while the whites and “free coloreds” revel below.

Shown in full shackles and headed for work, they appear too weary to pay heed to the ball. In turn, the revelers pay little heed to them.

Gabriel stands by with his trumpet, symbolizing the slaves’ longing for the next life. Understandably, as death was the only sure escape from their torment.

I love this quote I snatched from an “Art Buzz” article on Caribbean-Beat:

“Oftentimes we think of history as something we learn at school. When we look at works like Crichton’s, history comes alive in ways that are fascinating. They’re paintings about history. But they’re very much alive, contemporary works.” ~ Art critic Eddie Chambers

If you’ve visited Jamaica, you’re aware it’s a Mecca for tourists. But there’s so much more to the island than its beaches, and it’s worth taking a step past its shoreline to catch a glimpse of its past. One way or another, we (i.e. our ancestors) all played a part in it. I hope Crichton’s work has sparked an interest, and you’ll take that step on your next (or first) visit.

Ms. Crichton tells me that The Nugents Entertain at King’s House is also reproduced in the new addition of Jamaican Art Then & Now! You can see other intriguing depictions of her work on her website, and I encourage you to check it out.

Many of the images in the Ms. Crichton’s collage echo the themes and historical details in Voices Echo.

Many of the images in the Ms. Crichton’s collage echo the themes and historical details in Voices Echo.

- Nugent, Maria, as edited by Philip Wright. Lady Nugent’s Journal of Her Residence in Jamaica from 1801 to 1805. The University of West Indies Press, 2002 p 65

- Ibid., p XXIX

- Kriz, Kay Dian. Slavery, Sugar, and the Culture of Refinement, Picturing the British West Indies, 1700-1840. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008 p 133

- Ibid, p. 131

- Surviving written accounts characterize the festival as non-religious in nature. Those writers, however, were all European, and it’s possible they hadn’t attained a clear understanding of the celebration’s significance to the Africans.

Thank you for providing us with a decisively informative account of the times and insight into this artist’s research and deliberation. So impressive.

I’m so very proud to at least share her birthplace.

Thanks for your comment, Christine. It was a joy to correspond with Carol, and her work is impressive!

Thank you, Linda Lee Graham, for your very detailed, revealing and interesting analysis of Carol Crichton’s splendid painting, The Nugents Entertain at Kings’s House.

Ms. Crichton very beautifully, thoughtfully and uniquely fused art with history. It is an illuminating depiction of the past that today still haunts Jamaican society. I congratulate her wholeheartedly!

You’re welcome, Carole. Every time I look at that image, I’m impressed all over again with how much she conveyed.

Could you supply a jpg of Lady Maria Nugent for use in my book, Caribbean Women’s Art?

Mary Ellen Snodgrass

5591 Ashley Court

Hickory, NC 28601

828-324-0155

aphra@charter.net

Hi, Mary Ellen. I’m unable to comply with your request as the image is not mine. However, Carol may be happy to share it, so please don’t hesitate to contact her. Her website is: http://www.carolcrichton.com/