Federal Procession

of 1788?

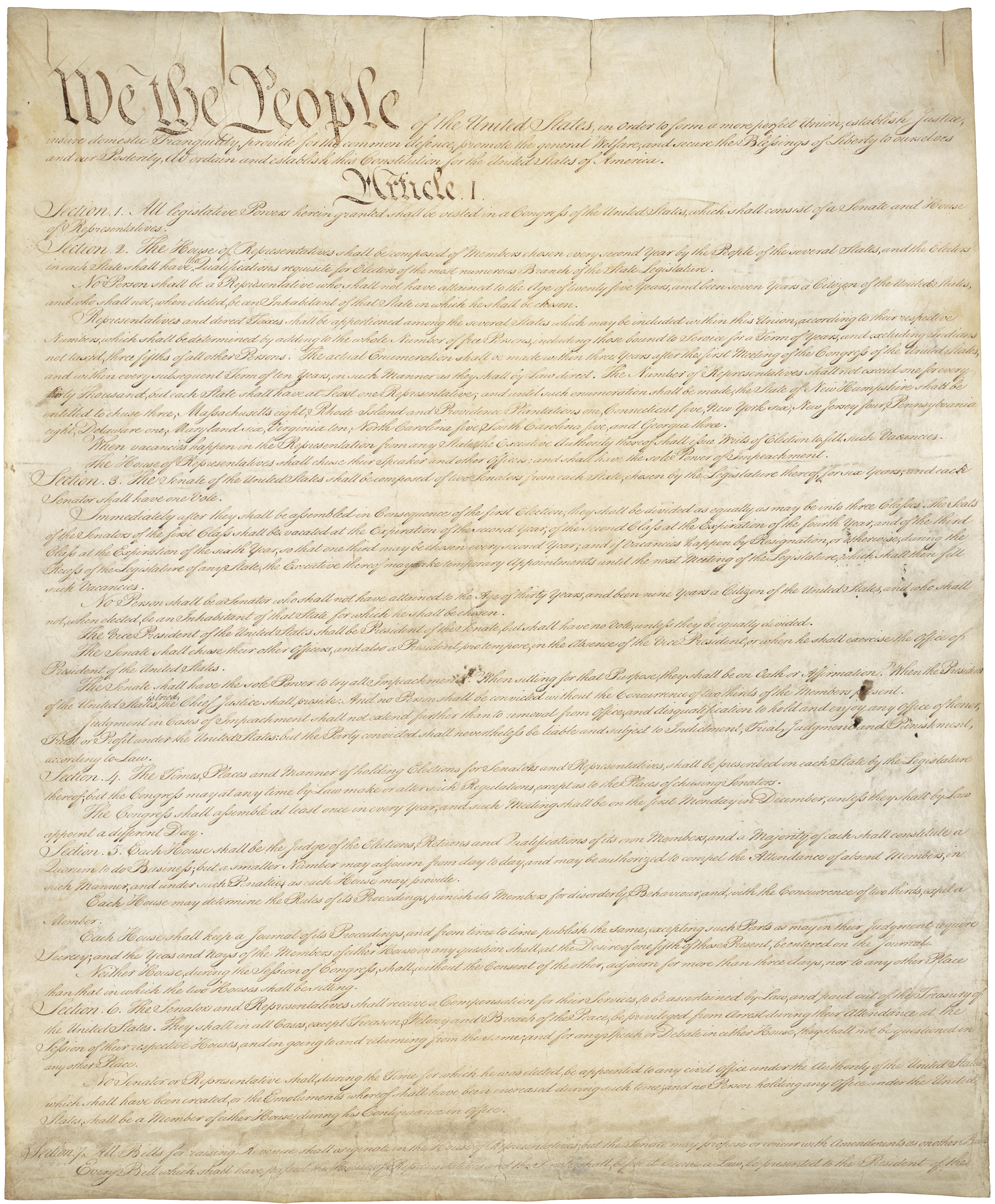

The principal purpose of the Federal Procession was to honor the newly ratified United States Constitution.

The Rocky Road to the Constitution’s Ratification

The United States Constitution was signed in September, 1787, but it wasn’t the law of the land. Nor would it be, until at least nine of the thirteen states ratified the document.

Persuading nine states to ratify was not easy.

The arguments for and against ratification were heated and divisive.

Therefore, some of the best minds in the nation joined forces to convince the populace of the Constitution’s merits.

“We won the war. What was it all for? Do you support this Constitution?”

~Lyrics to “Non-Stop,” Hamilton, The Musical

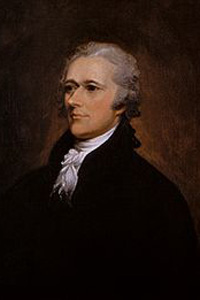

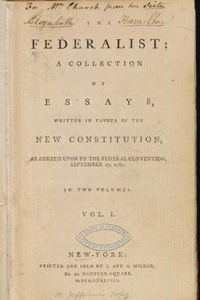

In New York, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay anonymously penned a series of eighty-five essays in favor of ratification. The essays were combined into a publication named The Federalist.

Thereafter, those supporting ratification of the Constitution came to be known as Federalists, and those against its ratification were known as Anti-Federalists.

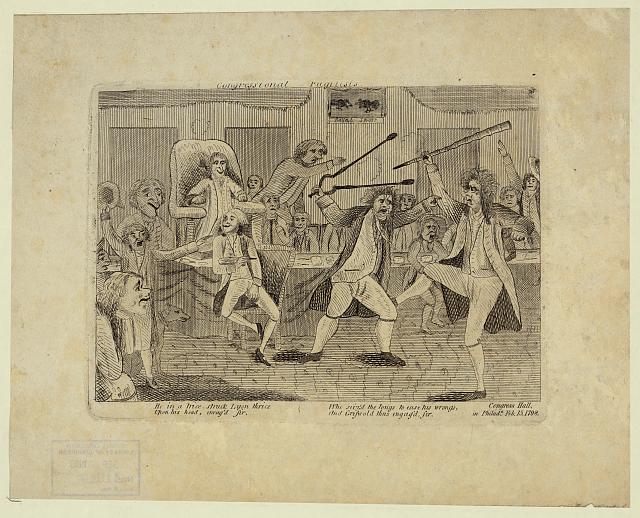

The animosity between these two groups easily rivals any animosity between today’s political parties.

Nevertheless, by June 21, 1788, the Federalists achieved their objective. The last of the required nine states signed. A tenth, Virginia, signed on June 25, 1788.

So, to commemorate, Philadelphia planned a celebration that would rival any the new nation had seen before.

Francis Hopkinson

The announcement, planning, and exhibit building took place in under two weeks.

The Planners

One of the most extraordinary things about this story is that it took under two weeks to both plan and implement the Procession!

Francis Hopkinson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was one of the principal planners. In addition to writing an ode, he helped design the Grand Federal Edifice, the parade’s centerpiece.

Benjamin Franklin Bache, Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, published a broadside listing the order of the procession.

Alexander Reinagle, a musician, wrote the Federal Grand March in a matter of days.

Artist Charles Wilson Peale provided flags of all America’s allies. He also aided in the design of costumes, banners, and mottoes.

And, perhaps most impressive, representatives from forty-four trades and professions set aside their daily routine and paid livelihoods in order to prepare their own parade entries.

Charles Wilson Peale

Alexander Reinagle

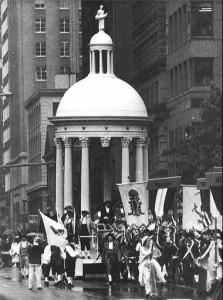

The grandest exhibit might have been the Federal Edifice. Hopkinson described it thus:

“The new roof, or grand federal edifice, on a carriage drawn by ten white horses; the dome supported by thirteen Corinthian columns, raised on pedestals proper to that order; the frieze decorated with thirteen stars; ten of the columns complete, and three left unfinished: on the pedestals of the columns were inscribed, in ornamented cyphers, the initials of the thirteen American states. On the top of the dome, a handsome cupola surmounted by a figure of Plenty, bearing her cornucopia, and other emblems of her character . . . Round the pedestal of the edifice were these words, ‘in union the fabric stands firm.’ ” — Francis Hopkinson

“Rank for a while forgot all its claims.”

The Participants

A cast of thousands, from all walks of life and religions, participated in the event.

Every trade and profession in the city, every resource, every talent, and every class must have worked each day and night of those two weeks to make the event a success.

Not for private gain, but for a tribute to their new country.

With a minimum of the usual fuss and preliminaries, Americans’ energy and determination accomplished the near impossible; it was nothing less than astonishing.

I have to believe that mutual respect and cooperation were evident in each and every step of the planning–how else could they have pulled it off in such a short span of time?

The Parade

Benjamin Rush wrote that “every countenance wore an air of dignity as well as pleasure. Every tradesman’s boy in the procession seemed to consider himself as a principal in the business. Rank for a while forgot all its claims, and Agriculture, commerce and Manufactures, together with the learned and mechanical professions, seemed to acknowledge, by their harmony and respect for each other, that they were all necessary to each other, and all used in cultivated society.”

The first cannon discharged at sunrise, accompanied by the toll of the bells of Christ Church. The call could be heard for miles, and all of Philadelphia answered, filling streets that had been tidied and trimmed the day before. The parade began at 9:30 the morning of a cloudy, cool summer day.

Ten vessels ran the length of the harbor, from the Northern Liberties all the way to South Street, and each flew a white flag at the masthead, calling out in gold letters the name of a ratifying state beginning with the northernmost and progressing to the southernmost. All the other ships in the anchorage were dressed as well, and nature accommodated with a brisk wind from the south that kept the flags and pendants flying large for all to view.

The marchers covered about three miles, most of it in silence. Written accounts record that the spectators viewed the parade in quiet awe, with joy and pride on most every face.

Federalist or anti-Federalist—the labels were forgotten for a brief while. All were Americans for the day.

Bush Hill 1793 Free Library of Philadelphia, Print & Pictures

The After-Party

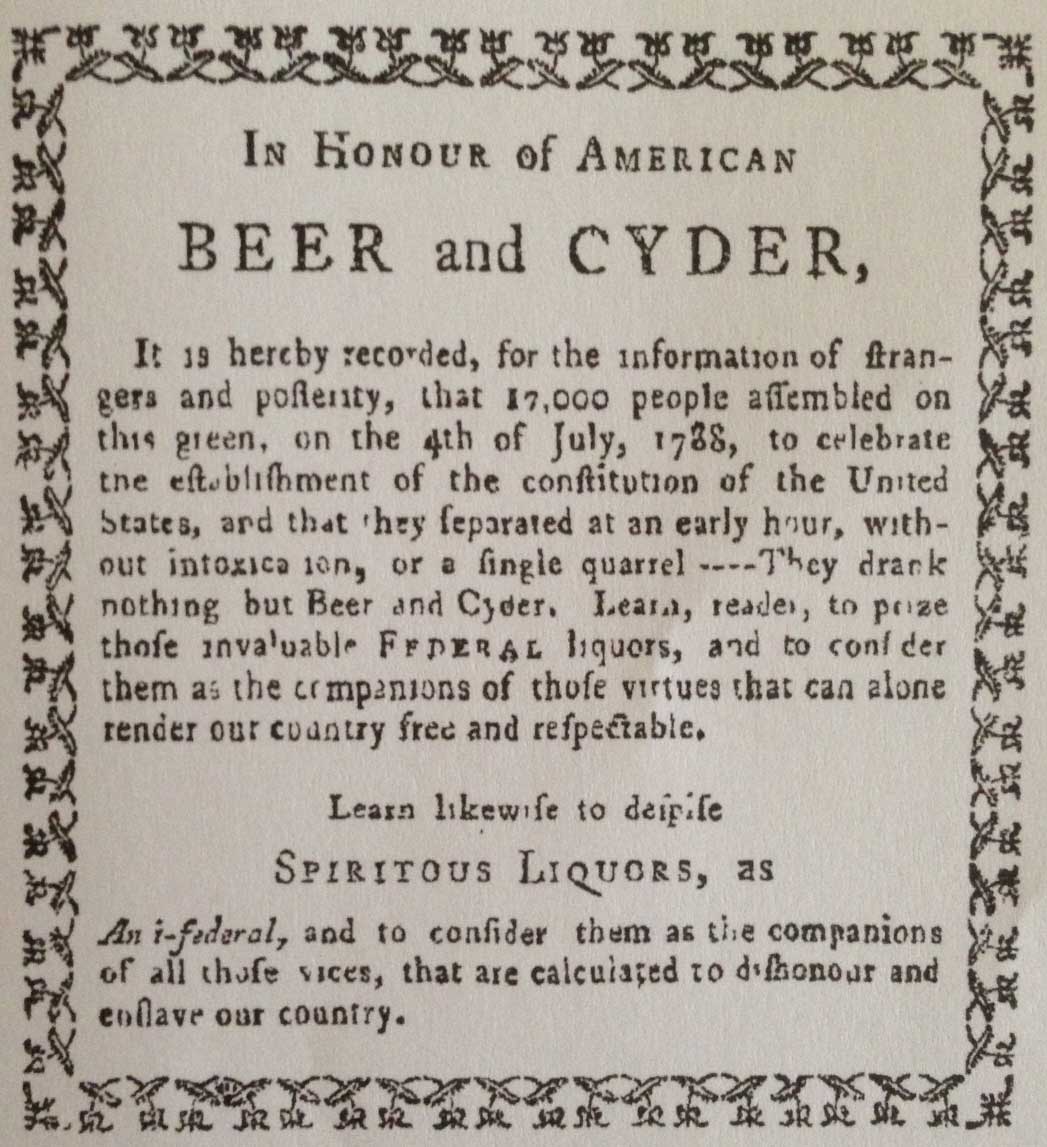

Following the Federal Procession, the revelers gathered for food and drink at Bush Hill.

One attending Philadelphian, seeming a bit obsessed with the libations, recorded the following:

” . . . to relate one more fact, from which I derived no small pleasure, or rather triumph, after the procession was over. It is, that out of seventeen thousand people who appeared on the green, and partook of the collation, there was scarcely one person intoxicated, nor was there a single quarrel or even dispute, heard of during the day. All was order, all was harmony and joy.

These delightful fruits of the entertainment are to be ascribed wholly to no liquors being drank on the green, but BEER and CYDER. I wish this fact could be published in every language, and circulated through every part of the world, where spirituous liquors are used . . . Since writing the above, I have been informed, that there were two or three persons intoxicated, and several quarrels on the green but there is good reason to believe that they were all occasioned by spirituous liquors, which were clandestinely carried out, and drank by some disorderly people, contrary to the orders of the day.”

(No doubt those “disorderly people” were Anti-Federalists! 😉)

The Aftermath

Finally, as night fell, lanterns were lit and hung from ships’ masts, and before long, the harbor glittered in celebration.

Aurora Borealis (1865), by Frederic Edwin Church

Mother Nature even pitched in, bestowing her own tribute with a display of Aurora Borealis.

What more could one ask?

A coming-of-age novel, Voices Beckon is set in 1780s Philadelphia, immediately after the Revolution. In addition to having a strong romance thread, the book captures the conflicts and tension in the new United States from the time of the Articles of Confederation to the writing and ratification of the Constitution.

“Davey, ye must participate. This is an opportunity that will not come twice.”

“I doubt that. The country will likely have Independence Day parades for the next twenty years.”

“Not like this, not like the one celebrating the first year of our new Constitution.”

- Francis Hopkinson, Account of the grand federal procession, Philadelphia, July 4, 1788. To which are added, Mr. Wilson’s oration, and a letter on the subject of the procession Philadelphia 1788

- David O. Stewart, The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution, New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007