I booked airline tickets to Glasgow recently, from the comfort of my office chair, with the convenience of my charge card. No sooner had I clicked the ‘book it’ button, did I begin to dread the thought of the inconvenient delays at the airport, the long security lines, the lousy food I’d be offered (would they offer decent wine?), and the four inches of leg room I’d be allotted in the seven-plus hours it would take to fly from Philadelphia to Glasgow. Prone to travel sickness, I made a mental note to purchase Bonine. And geez, how many months would it take to pay off this charge? Why didn’t I calculate that before I clicked the button?

Wow . . . I think perhaps I’ve lost my perspective.

Would my inconvenient delay involve waiting for days, maybe even weeks—long past the time my meager budget for lodging had been depleted—while the powers that be waited for a favorable wind?

Would I stand in line at the harbor for hours, only to find when I had finally reached the front, that the ship was already full? Or that the ticket I’d purchased this morning was for a ship that had sailed yesterday?

Would my food for the next six to twelve weeks be unrefrigerated, several years stale, or contain maggots? Would my water have come straight from the foul river, poured into a filthy cask half full with water remaining from the last voyage?

How many passengers would share my six by three berth? Two? Three? Would they have lice? Would I disembark with lice as a result?

Would I contract typhus, dysentery, or smallpox?

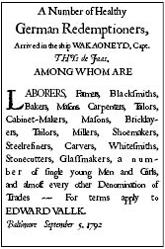

Many of those immigrating to America paid via indentured servitude, not American Express. They sold their future services for a number of years—years, not months—to an American looking for a servant. Would I be committing years of my paycheck in exchange for this ticket?

Thankfully . . . no. To all of the above.

An Eyewitness Account

Gottleb Mittelberger, a German schoolmaster, traveled from Europe to Philadelphia in the mid 1700s. His diary left a vivid eyewitness account of the journey:

“. . . during the voyage there is on board these ships terrible misery, stench, fumes, horror, vomiting, many kinds of seasickness, fever, dysentery, headache, heat, constipation, boils, scurvy, cancer, mouth rot, and the like, all of which come from the old and sharply-salted food and meat, also from very bad and foul water, so that many die miserably.

Add to this want of provisions, hunger, thirst, frost, heat, dampness, anxiety, want, afflictions, and lamentations, together with other trouble, as e.g., the lice abound so frightfully, especially on sick people, that they can be scraped off the body. The misery reaches a climax when a gale rages for two or three nights and days, so that every one believes that the ship will go to the bottom with all human beings on board. In such a visitation the people cry and pray most piteously.

No one can have an idea of the sufferings which women in confinement have to bear with their innocent children on board these ships. Few of this class escape with their lives; many a mother is cast into the water with her child as soon as she is dead. One day, just as we had a heavy gale, a woman in our ship, who was to give birth and could not give birth under the circumstances, was pushed through a loophole (porthole) in the ship and dropped into the sea, because she was far in the rear of the ship and could not be brought forward.”

Other diaries from the eighteenth and early nineteenth century survive as well, and the theme of misery in the crossing is commonplace in all. The man wasn’t exaggerating.

I’d wager that in 200 years people will be able to reach the other side of the world in a matter of minutes, even seconds, straight from home. How, I don’t know, but I’ll bet they will.

I wonder if they’ll whine of the slight headache experienced as a result of such flash travel. Again, I’ll bet they will.

“We’ll be in Philadelphia by nightfall, Liam. What’s the first thing ye plan to do?”

“Eat.”

David laughed. “Aye. And drink. A full pint of anything wet not laced with vinegar or tar.” ~ Voices Beckon

“Passage to America, 1750,” EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2000).

Edwin C. Guillet, The Great Migration, The Atlantic Crossing by Sailing-Ship 1770-1860 (Canada 1967)

OMG, all that and childbirth, too. And I thought being seasick on an Atlantic crossing was as bad as it gets.

No kidding! I know I couldn’t have done it. Thanks for dropping by, Jean.

Zounds, lass! I didna ken ye could write so well.

Much to my surprise, I enjoyed the book (I’m not a Romance fan).

But I am a big fan of American History from the Revolution to the Civil War. Good character development and storyline.

Nice work! I’m impressed.

My ancestors immigrated from Germany to America in 1847. I’ve been trying to get a good description of what their Atlantic crossing most probably entailed (time, conditions, personal belongings, etc.). Can I access any of the 1800 diaries that are mentioned above? I would also like to find information on how immigrants traveled from their European homes to their ports of departure. Thank you in advance for any assistance you may provide.

Hi Mike — I may be able to point you in a couple of directions that might help. I’ll dig through my notes and get back to you.

Hi Mike:–I’m interested in the same data. My ancestors immigrated from Germany in 1850 [From Bremen to NY on the bark Caroline arriving on 8 May 1850. What were you able to find?

Now take all that and imagine coming across the Atlantic as a slave!

Supposedly one of my ancestors sailed from Rotterdam to Philadelphia on the ship, Windsor, that landed 26 September, 1753. All this misery described above just to immediately start work as an indentured servant to pay for the privilege of the voyage / ordeal.

I give thanks to all who survived so we can live in such a great country.

It sounds as if you have great family records. I’m envious!

My ancestors sailed from Bremen Haven (March 1847), whichn after much research, appears to have been one of the more ‘enlightened’ ports at that time. The ‘Bremen senate’ passed ordinances listing a number of requirements that most probably contributed to a tolerable trip. They came on the Barque Von Vincke and entered the United States at New Orleans. So far, unable to determine if they were ‘Steerage’ or in cabins on the upper deck. Am astonished there appears to be no ‘ocean stories’ handed down through the generations, even though an Annual Gottlieb and Dorothea Kaufmann reunion has been held for the past 103 years! Was it so horrific they were unable to share their experience?

Maybe the situation was more a matter of course, and your ancestors didn’t bother to document it. But if they did, I hope you eventually find it in some library archive!

In any event, family reunions for the past one hundred years plus is remarkable!

any first person sources from port of Hamburg mid 18th c?

Thank you

Diana Korzenik

My 8th great grandfather Philip Seifert landed in philadelphia on sept.25th 1749 on a ship called the speedwell with his 1 year old son Philip Jr. . He was only 18 years old and settled in berks Co. PA Near Reading

From nothing and built a home and large farm . the 1 year old ended up fighting in the revolution .. I can’t even imagine the hardships they endured .. most people here today don’t realize what people endured to make a life for themselves and future generations.

Can anyone tell me how much passage was to cross the Atlantic in a sailboat, from Liverpool to New York in 1860? Thank you

My 8th great grandfather Philip Seifert landed in philadelphia on sept.25th 1749 on a ship called the speedwell with his 1 year old son Philip Jr. . He was only 18 years old and settled in berks Co. PA Near Reading

From nothing and built a home and large farm . the 1 year old ended up fighting in the revolution .. I can’t even imagine the hardships they endured .. most people here today don’t realize what people went through to make a life for themselves and future generations.

I love stories like yours, Richard! Thank you for sharing it.

So glad to find this site! I am trying to determine how the DeMeuron soldiers who enlisted in Malta in 1813 traveled to Canada for the War of 1812 in 1813. They fought at the Battle of Plattsburgh. I am trying to find the size of the sailboat on which they and their families traveled. It appears that only boats, with sails were available when they left Malta on May 5, 1813 bound to Gibraltar and then on to Halifax, Canada. Was there room below deck where they could sleep? Or did they stop every night at ports en route? If the latter, which ports were they? Were they ports on the north shore of Africa? There was a yellow fever plague in Gibraltar at the time so I doubt that the travelers got off the boat.

That may be difficult, Diana!

OliveTreeGenealogy.com states “There are no comprehensive ships passenger lists of immigrants arriving in Canada prior to 1865. Until that year, shipping companies were not required by the government to keep their passenger manifests.” But you might narrow your search if Canada recorded at the names of ships entering its waters. Also, if you haven’t yet, be sure to check contemporary newspapers for shipping news.

Good luck!

My ancestors came over on slave ships, that was much worse.

I am looking for the same kind of original source material: Atlantic crossing, preferably from Portsmouth, England, to New York City in 1830. Any suggestions would be much appreciated, and credited in my work when published.

I am looking for the same kind of original source material: Atlantic crossing, preferably from Portsmouth, England, to New York City in 1830. Any suggestions will be credited in my work when published.

My Great Grandfather was born on a ship in 1859, coming from England going to Canada. It’s hard to amassgen what my great, great grandmother went through acrossing the atlantic in the mid 1850’s and pragent.

But now I have a better idea after reading this story.