An Eighteenth-Century Armour

Known as redingotes d’Anglaise (English raincoats) by the French, and baudruches (French letters), armour, sheaths, and machines by the English, condoms were a booming trade in eighteenth-century London. No matter the dire warnings from the Church, condemning the condom as immoral, and no matter the occasional prominent physician who blasted it as useless, an ever-growing demand created the potential for profit. Whenever that’s the case, commerce finds a way to thrive.

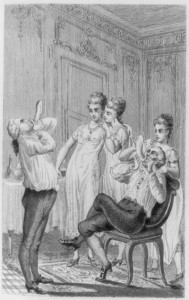

A Sale of English Beauties in the East Indies ~ James Gillray 1786 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Although its value as a contraceptive was known, evidence suggests its primary use was as a preventative. The threat of contracting “the great pox” was a very real concern in the 1700s.

There was no effective cure for the pox, so the promise of prevention was enticing. Payment could be high for that one quick indiscretion while out carousing with one’s mates—and if a lad had a friend, a sailor for Pete’s sake, who’d vowed he’d been using condoms for years with no sign of the dreaded pox—why wouldn’t he be tempted to consider the condom as well?

Hawked Streetside

London entrepreneurs, not a few of them women, sold their wares in taverns, pubs, barbershops, and apothecaries, as well as hawked them streetside and in open-air markets. See the bale beside the auctioneer in the image above? If you look very closely, you’ll note it’s labeled ‘Mrs. Phillips (the original inventor) Leicester Field London. For the use of the Supreme Council’. Mrs. Phillips was one of the more famous 18th-century condom sellers.

Folding Your Own

The steps were simple:

- Soak the intestines in water for several hours.

- Soften the mess by soaking it in a weak lye solution for a day or two, changing the solution every twelve hours.

- Scrape the mucous membrane off the intestinal material.

- Soften the remaining matter over the vapor of ‘burning brimstone’ (steam it over hot sulfur).

- Wash what’s left with lye soap and water.

- Cut into oblong-shaped pieces and fold up into a sack (about seven inches should do, maybe eight).

- Punch tiny holes around the top edges and thread the ribbon (pink was especially popular) through those holes.

Voila! One size fits all.

For the truly ambitious, the moist gut in step six might be molded over an oiled glass cast that has been blown into the appropriate shape.

It’s best not to try any of this at home. The fumes from the sulfur and lye can cause debilitating side effects and the effort might result in a condom riddled with holes. (Hence Cananova’s Party Trick in the image to the right).

Visit the local drugstore instead.

The linen condom was easy to produce as well, provided one was proficient with a needle. But the trade found the gut variety sold better, as the seam on the linen condom proved uncomfortable to customers.

These little devices were expensive, and it was not uncommon for a man to save and reuse his armour. Buying, washing, and reselling used condoms evolved into a lucrative side occupation for those with ready access to a brothel.

The Trade Across the Pond

Now, why this surge of capitalism didn’t catch on in eighteenth-century Philadelphia, I’m not sure. It certainly wasn’t for lack of need. Immigrants from all over the world flowed into the city through its harbor, making Philadelphia the most ethnically and socially diverse city in the new United States, as well as the city with the closest ties to Europe. Venereal disease was epidemic during the last two decades of the 1700s, and casual sex, children borne outside of wedlock, adultery, and prostitution were commonplace.

Nevertheless, it was one industry in which it appears our American forefathers lagged behind. It may be that individuals made do with their own resources, or that the supply of black market condoms smuggled in by the carrying trade was sufficient to fill the demand. But for whatever reason, evidence suggests condoms were not sold openly on Philadelphia’s Market Street.

That began to change in the mid 1790s. Moreau de St. Méry, an ex-patriot from France, visited Philadelphia in 1793 and decided to stay. He opened a bookstore on Front and Walnut in 1794 and stocked it with condoms as well as books, thinking to provide for the French colonials. He soon found the small items to be in great demand by the Americans.

St. Méry credits himself that “the use of this medium on the vast American continent dates from this time.” And though happy to supply a need and make a profit, he did deride the American customers’ surreptitious purchase and use. By the time he closed up shop in the late 1790s, Philadelphians could make their discreet purchases in any number of establishments.

I think protection would have been on the mind of any randy young lad with a mind to his future, and Liam and David discuss the merit of black market condoms in Voices Beckon.

I think protection would have been on the mind of any randy young lad with a mind to his future, and Liam and David discuss the merit of black market condoms in Voices Beckon.

“Alex promised to bring a stash of condoms when next he arrives from London. Without taxes, the cost shouldna be too dear. Think of it as an investment in your future, Davey. Why, a careful lad like you, you could make one or two last a year.”

David grimaced. “The Kirk doesn’t condone the use of armour, Liam.”

“And it condones rogering thy neighbor’s wife? Why, ye are a veritable fountain of knowledge today.”

“Widow, not wife.”

“Ahh, a fine distinction, to be sure. Now see, I hadna known that. Leave it to the Kirk.”

David laughed. “Right then. I’ll speak to Alex next he comes.” Or maybe he’d do as he should and stay away from the whores. ~ Voices Beckon.

Collier, Aine, The Humble Little Condom, A History, (Amherst, New York 2007)

Lyons, Clare, Sex Among the Rabble, An Intimate History of Gender & Power in the Age of Revolution, Philadelphia, 1730-1830 (University of North Carolina Press, NC 2006)

St. Méry , Moreau de, Moreau de St. Méry’s American Journey (1793-1798), translated and edited by Kenneth Roberts and Anne Roberts, (Garden City, NY 1947)

Image of Market Street: Mather, Horace, Early Philadelphia: Its People, Life & Progress, (Philadelphia, PA 1917)