The story of well-traveled cobblestones paving America’s streets is a romantic one. But is it true? Did ballast rock from foreign ports pave America’s colonial seaport streets?

Ballast

Ballast is what’s carried in a ship’s hull so the ship doesn’t topple. Because an empty hull is overly buoyant, stowing weight in the hull adds balance and stability.

Optimally, a salable cargo solves the problem. Past trade imbalances, however, often dictated that a ship adjust its ballast at port. Thus a ship might take on additional ballast in Lisbon and deposit it in Philadelphia. Anything bulky or heavy qualifies as ballast, and stones were commonly used.

Paved Streets Uncommon

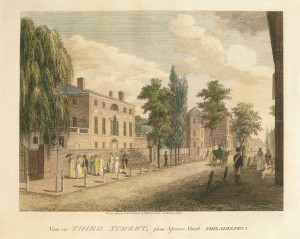

In most of the streets is a pavement of flags, a fathom or more broad, laid before the houses, and posts put on the outside three or four asunder.” Swedish traveler Peter Kalm of his 1748 Philadelphia visit

It was a struggle for a colonial city to finance a municipal project of any scope, including paying city streets. So in 1727, Philadelphia’s Municipal Corporation tried ordering residents to pave the footpaths in front of their property.1 Unfortunately, the city had no means to enforce the obligation, so it wasn’t a solution.

A Public Works Lottery

But in 1762, after thirty plus years of failed attempts, the city resorted to a tactic many states use today — a public lottery. Its purpose was to fund the act for “regulating, pitching, paving, and cleansing the streets, lanes, and alleys, etc., within the settled parts of Philadelphia.”2

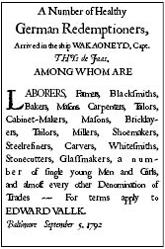

Philadelphia financed the project with its share of the lottery proceeds. The city’s next challenge was finding experienced pavers.

“The laborers employed on this work of paving were not very experienced, it seems, for on Purdon, a British soldier, related to John Purdon, store-keeper in Front Street, seeing how clumsily the men worked, offered to show them how to do it. He was a skilled pavior (sic), and his services became so much in demand that the city officials obtained his release from the army by paying a substitute to fill his place.”2

Paving stones for this project would have have been costly. Perhaps the stones used did travel from French, Spanish, and Dutch ports-of-call.

- Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. Weigley, Russell, editor. Norton & Company, NY 1982, p. 59

- Scharf, John Thomas and Westcott, Thompson. History of Philadelphia 1609-1884, Vol II. L.H. Everts & Co., Philadelphia 1884, p. 874