In eighteenth-century Jamaica, a creole was a nonindigenous person born on the island, whether of European, African, or mixed descent. Those referenced in the expression “as rich as a creole,” however, were invariably of European descent.

The phrase is a variant of the more familiar “as rich as Croesus,” implying a creole was as rich as Croesus, the ancient king of legendary wealth.

So what created such wealth on an island smaller than the state of Connecticut? In a word: sugar.

“They Could Scarcely Get Enough”

German monk Albert of Aachen wrote in 1100 of the Crusaders’ discovery of a refreshingly “wholesome . . . honey-flavored reed” in the Holy Land, that once tasted, “people could scarcely get enough of.” He also noted the cane’s cultivation required “extremely hard work on the part of the farmers.”1

German monk Albert of Aachen wrote in 1100 of the Crusaders’ discovery of a refreshingly “wholesome . . . honey-flavored reed” in the Holy Land, that once tasted, “people could scarcely get enough of.” He also noted the cane’s cultivation required “extremely hard work on the part of the farmers.”1

With uncanny perceptiveness, not only did Albert of Aachen discern sugar’s value, he pinpointed why the crop was a candidate for slave labor. Centuries later the nearly insatiable demand for sugar not only fueled the rise of the transatlantic slave trade, it fueled the creation of sugar tycoons.

Christopher Columbus brought sugarcane to the West Indies in 1493, on his second voyage. He was familiar with the crop’s potential; his first wife’s mother owned a sugar estate on Madeira.2

A Condensed Island History

Columbus claimed Jamaica and its indigenous people for the Spanish Crown in 1494, marking the beginning of its colonial history. Though colonized less rigorously than neighboring Hispaniola, Jamaica remained in Spanish possession for over 150 years, until Britain wrested the island from them in 1655.

The biggest of the British West Indian possessions, Jamaica quickly became Britain’s largest producer and exporter of tropical goods, with sugar at the forefront. By 1774, the island was the wealthiest colony in British America.

As rich as a Creole

Thousands of young Britons flocked to Jamaica in search of a fortune. The colony had an abysmally high mortality rate, but those who survived often achieved that fortune.

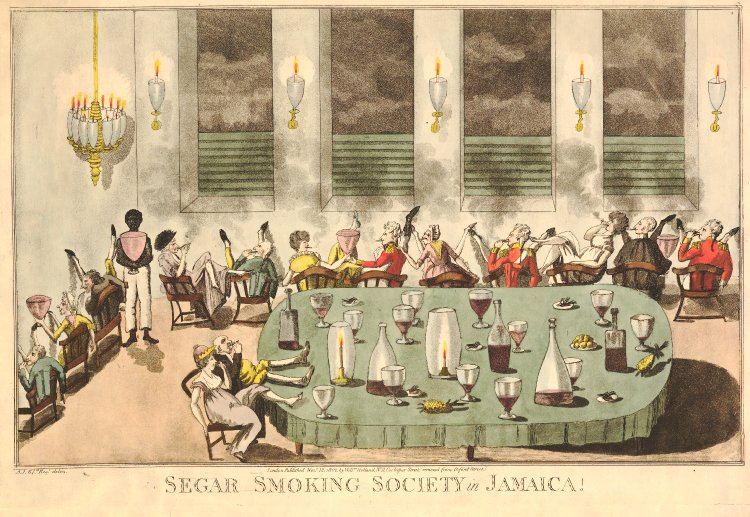

Segar Smoking Society in Jamaica James Abraham © The Trustees of the British Museum

Many wealthy planters, managers, and merchants spent lavishly and lived extravagantly. They became known for their ostentatiousness, and for a time “as rich as a creole” became a commonplace expression. King George III, upon spying the opulent coach and equipage of one such over-the-top West-Indies planter, was said to have noted it. In apparent concern that the Mother country might not receive its fair share of the wealth, he remarked to his minister: “Sugar. Sugar. Eh! All that sugar. How are the duties, eh, Pitt? How are the duties?“3

But at what cost?

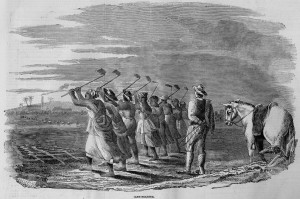

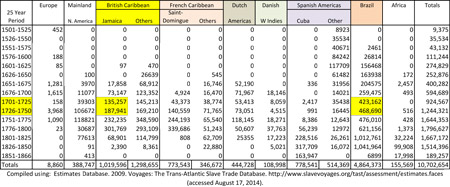

As Albert of Aachen wrote hundreds of years earlier, sugarcane cultivation was a slow, labor-intensive process. The West Indies planters came to rely almost entirely on imported slave labor to harvest and process the cane. From 1700 to 1750, Jamaica was second only to Brazil in the number of slaves imported from Africa.4

The Africans contended not only with the island’s climate and tropical diseases, but with an inadequate diet, an unrelenting labor regime, and the slave owners’ brutality. The island’s enslaved labor force never became self-sustaining as deaths far out-numbered births.

The Africans contended not only with the island’s climate and tropical diseases, but with an inadequate diet, an unrelenting labor regime, and the slave owners’ brutality. The island’s enslaved labor force never became self-sustaining as deaths far out-numbered births.

But perhaps most devastating, in that its effect was (or is) longer lasting, was the damage to the black creole’s psyche. Generations of children were born into slavery, and they grew up believing their skin color consigned them to the status of chattel.

The whites did not escape unscathed. The corrupting, barbaric effect of slave ownership cannot be underestimated. The circumstances altered the slaveholder’s behavior and core beliefs, making a mockery of any previously held cultural values.

Scholar Trevor Burnard, in his intriguing analysis of slaveholder Thomas Thistlewood’s diary, states:

“The foremost characteristic of white Jamaicans, therefore, was an all-consuming ambition for wealth, an avaricious and aggrandizing self-interest . . . Jamaicans were addicted to ostentatious display and devoted to luxury. They spent their money on lavish feasting, copious drinking, and all manner of sexual and sensual delights.” 5

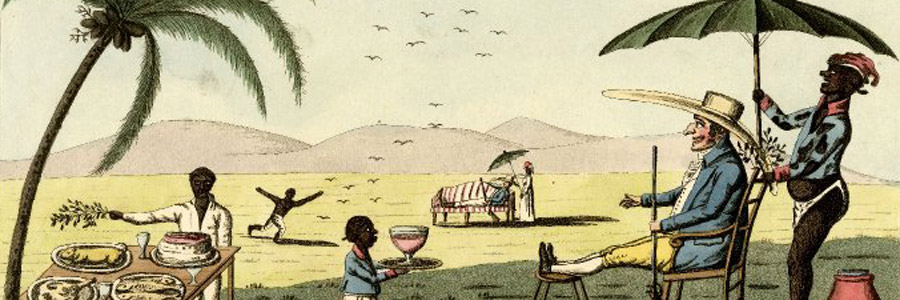

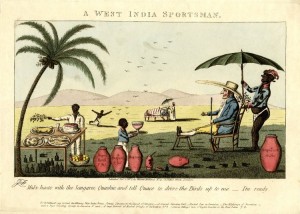

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The image at left is one of the many contemporary satirical prints mocking the indolence of West Indies planters. It is captioned: “Make haste with the Sangaree, Quashee and tell Quaco to drive the Birds up to me – I’m ready.”

The “sportsman” (planter) sits in a chair with his feet supported on a stool, gun in hand. A slave stands behind him with an umbrella to ward off the sun and a branch to beat off the flies. A boy approaches his master, his tray laden with an enormous goblet of sangria. Judging by the number of bottles, jugs, and plates filled with food, the planter has been at it a while. A fellow sportsman, this one reclining, is shown in the distance.

Unlimited power is apt to corrupt the minds of those who possess it.” William Pitt, Earl of Chatham 1770

Part of this self-indulgence might be attributed to a desire to live in the moment. Good health was fleeting in a way that’s impossible to appreciate today. Add to that, the whites were heavily outnumbered. Fear the enslaved would revolt and extract revenge was ever-present.

The Fall of Planter Society

For a number of reasons, by the end of the eighteenth century the growth of the planters’ debt began to outpace the growth of their wealth.

In 1807 the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act abolished slave trading in the British Empire, effectively numbering the days of slavery in Jamaica. In 1834 Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act abolished the practice of slavery in most of their possessions.

Jamaica herself gained independence over a century later, in 1962.

In Voices Echo, Liam Brock struggles with the temptation to let others handle life’s unpleasantries:

Outside the stable, Liam paused mid-step, considering. Had the day come when he couldn’t be bothered to unsaddle his own horse? Nay, not even that—a horse not his to begin with, but one he enjoyed freely.

Perhaps it had. Dripping wet, he was anxious to escape the mosquito-laden, steaming inferno of a stable. He started toward the house again.

Hell, he may be dripping wet now, but as soon as he went inside, he’d no doubt find dry clothes laid out and waiting, ready for use. His pot of shaving cream, scented with some concoction the lovely mistress of the plantation had prepared especially for him, would be restored from this morning’s use and set alongside a freshly honed razor for his beard and newly cut root for his teeth.

How quick the slide to pampered fool. Rhiannon had been right. Plantation life changed men—and not for the better. He retraced his steps. ~Voices Echo

———————————————

1“Sugar.” In Africana The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, edited by Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., 1800. 1st ed. New York: Basic Civitas Books, 1999.

2Crosby Jr., Alfred W. “Old World Plants and Animals in the New World.” In The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492, 68. 30th Anniversary ed. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2003.

3Sheridan, R.B. (1961), “The Rise of a Colonial Gentry: A Case Study of Antigua, 1730-1775.” The Economic History Review, 13: 342–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0289.1961.tb02124.x

4 Table below compiled using: Estimates Database. 2009. Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. https://www.slavevoyages.org/tast/assessment/estimates.faces (accessed August 17, 2014)

5Burnard, Trevor G., Mastery, Tyranny, and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and His Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004. 19.