Kara Walker’s “Subtlety” is Anything But

Appearances notwithstanding, it’s safe to say Kara Walker didn’t intend to present a sugarcoated history when she created her cast of sticky subtleties in the defunct New York Domino Sugar refinery earlier this summer.

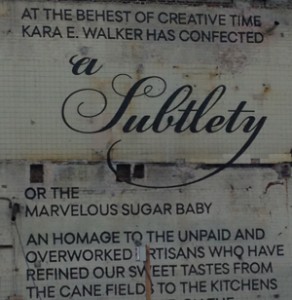

Her remarkable two month long exhibit, entitled “A Subtlety,” was billed instead as a homage to all the “unpaid and overworked artisans” who labored the sugarcane fields in days past.

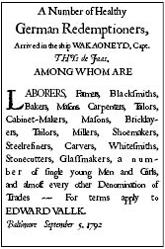

Unpaid artisans . . . ? Yes, she’s referencing the enslaved—and offering a not-so-subtle clue that her exhibit targeted the horrors of the 18th-century West Indies slave trade.

Inside the Refinery

The soon-to-be demolished refinery closed in 2004, but a dark and sticky molasses and sugar residue still clung to the walls ten years later, adding an authentic aura and odor to the exhibit.

The soon-to-be demolished refinery closed in 2004, but a dark and sticky molasses and sugar residue still clung to the walls ten years later, adding an authentic aura and odor to the exhibit.

A few steps inside the building and a visitor came face to face (or face to nipple) with a snow-white, towering, majestic sphinx. Stretching seventy-five feet long and thirty-five feet high, the sugarcoated sphinx dominated the cavernous factory.

-

Kara Walker’s Sugar Sphinx

“What we’re seeing, for lack of a better term, is the head of a woman who has very African, black features,” Walker explained in a NPR interview. “She sits somewhere in between the kind of mammy figure of old and something a little bit more . . . recognizable . . . recognizably human . . . She’s positioned with her arms flat out across the ground and large breasts that are staring at you.”

The sphinx was settled in the traditional pose with the exception of a raised tail-end. That raised tail-end exposed a giant vulva. Make of that what you will; there were no edifying placards placed beneath her. To me, it more than hinted of the rampant sexual exploitation of enslaved women during sugar’s heyday. And as it turns out, Walker’s art is noted for exploring the “vestiges of sexual, physical, and racial exploitation” of slaves. (NY Times)

Kara Walker’s Sugar Baby

In the early days of the exhibit there were fifteen cherubic sugar-boys (babies) lining the walk to the giant sphinx. Unsurprisingly, all did not survive the duration of the exhibit. Made of candy, many melted in the summer heat.

Their fate was yet another not-so-subtle subtlety. The mortality rate of those working the cane-pieces was abysmally high, and the harsh climatic conditions with its accompanying diseases was one of the reasons.

Ms. Walker, in a move she admits was “maybe a little bit hammer-over-the-head,” took some of the pieces of the melted, broken boys and threw them “into the baskets of the unbroken boys.”

A gut-clenching reminder of a sugar plantation’s “bloody sugar day,” wherein a slave charged with hastily feeding cane into the mill would lose a limb between its crushing rollers.

What does it all mean?

I didn’t attend the exhibit but my daughter did, and she shared her photos and first-hand impressions. Art means different things to different people, but for what it’s worth, the message I absorbed was one not only of overwhelming loss and sadness, but of survival.

Wearing a kerchief and exaggerated African features, the towering white sphinx conveyed an overwhelmingly powerful figure. Take from her what you will, she’ll not be cowed into surrendering her essence.

And the dripping, black, molasses-covered boys carrying the baskets? Their image exudes a  heart-rending vulnerability, and it’s as simple as that.

heart-rending vulnerability, and it’s as simple as that.

By all accounts, A Subtlety was a powerful exhibit. Read the New York Times and NPR interviews with Ms. Walker and watch the video below for more insight.

As an aside—or maybe not an aside, as the subtleties of medieval times were what inspired Walker—“subtlety” is an historical term for an ornamental confectionery table decoration. It was usually made of sugar and often eaten.