Yesterday’s Tabloids

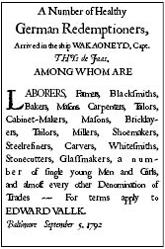

Simple and cheap, broadsides were a common means of communication for close to three hundred years, up through the early 1800s. They were first used to post notices of royal proclamations and later expanded into notices of events, advertisements, ballad sheets, and political commentaries. Illustrations made from woodcuts were common, as pictures added interest.

Liam had forgone the usual depiction of the accused hanging from the gallows. Instead he’d fashioned a woman with her baby at breast. Somehow, he’d managed to convey love, adoration, and devotion with a few deft swipes of his knife . . . Voices Whisper

The broadsheet may have been posted, or it may have been distributed by hand. Competition was fierce among printers, and they often relied on hawkers to distribute their wares and to do so speedily. The first with the news was usually the one who reaped the highest rewards–some things don’t change over time.

An actual broadside is simply a large sheet of paper, and is usually printed on one side only. In the past it was typically priced at a penny or less and was a publication most of the common folk could afford.

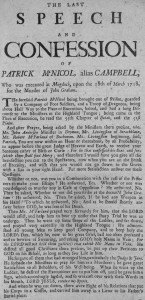

An Execution Broadside

In spite of their ephemeral nature, some historical broadsides still exist and are a fascinating read for anyone with an interest in life of days past. Popular events included public executions, and printers counted on people splurging for a broadsheet that gave an account of not only the execution, but of the sensational events that led up to it.

The image at the left shows a broadside from 1718, and it details the last speech of Patrick McNicol (Campbell) before he was executed for the murder of John Graham at Mugdock, near Glasgow, Scotland. (It also advertises his confession, but as Mr. McNicol denied everything but an escape from prison, I wouldn’t consider it a confession to the murder, but more of a confession to God.)

Once McNicol finished speaking with the clergy, he began his climb up the ladder to the noose. Halfway up he paused and sat, taking advantage of his captive audience to admonish all young men to keep good company and to heed the dictates of their religion. Or so says the writer.

Eight of McNicol’s family were present to place his corpse in a coffin and carry it to his father’s burial place. It’s interesting the broadside specifies several times that the man spoke in the “Highland Tongue.”

The McNicol broadside is somewhat tame compared to others still available. I choose it because the execution took place at Mugdock, a former stronghold of the Grahams in Scotland.

An execution broadside would typically offer a detailed account of the crime and the trial–it might portray the perpetrator as evil incarnate, or it might be written to elicit sympathy. More than one version might be offered at the site of the execution, and more often than not all versions would carry a religious bent, invariably cautioning the reader against following a similar path.

The woodcut was impressive as hell, as were all the man’s carvings. Readers would go wild over the contradiction—a mother’s love up against the charge of infanticide . . . from Voices Whisper

Decline of the Broadside

By the mid-nineteenth century, increased literacy, advances in the printing industry, and reductions in the newspaper tax led readers away from broadsides and towards newspapers. For those whose reading taste still veered toward the salacious, the penny dreadfuls were coming into fashion and were an affordable alternative.

In Voices Whisper, David’s goal was to use his broadsheet to elicit sympathy for Tom’s daughter. However, he was savvy enough to recognize the opportunity for a profit. He did what he could to have his broadsheet, enhanced by an original illustration courtesy of Liam, ready for a hawker to sell the scheduled day of execution.

The woodcut was unusual and would indeed fill a good quarter of a broadsheet. Impressive as hell, as were all the man’s carvings.

“Who did the woodcut?” the printer asked. “One from her family?”

“Nay, my mate did,” David answered. “He’s never met her.”

“Hmmph.” The printer looked at him, his eyes gleaming as if he were calculating his share of the profits. “If you decide it’s to be printed, I think we best print a few hundred more than you’d contracted for.”

Liam had forgone the usual depiction of the accused hanging from the gallows. Instead he’d fashioned a woman with her baby at breast. Somehow he’d managed to convey love, adoration, and devotion with a few deft swipes of his knife. David knew what McAllister was thinking. Readers would go wild over the contradiction—a mother’s love up against the charge of infanticide.

Tweetables to click and share: